Covering Balconies with Pimapen: A Subcultural Phenomenon

The urbanization process in modern Turkey has been marked by the expansion of cities from their historical core to the periphery, a phenomenon largely driven by internal migration from rural to urban areas in the mid-twentieth century. This process was characterized by the construction of houses, commonly referred to as gecekondu, which were built by immigrants using their own financial resources and labor. Gecekondu not only served as a means of shelter but also contributed to the creation of a unique spatial subculture that persists to this day.As urbanization progressed and gecekondu gave way to apartment buildings, the traces of this subculture could be observed in details such as spatial economy, functional preferences, and construction materials. One notable example of such materials is PVC, commonly known as “Pimapen” in Turkish, which has left an indelible mark on the country’s built environment. Pimapen is widely used due to its affordability, accessibility, and flexibility in redefining spatial boundaries.This study focuses on the practice of covering apartment balconies with Pimapen, a phenomenon that has become increasingly common in Turkish society. By exploring the social and cultural implications of this practice, the study sheds light on the complex relationship between form and function, subculture and mainstream culture, and tradition and innovation in Turkey’s evolving urban landscape.

Problematization

A few years ago, my acquaintance Nagihan and I were taking a respite in Kocamustafapaşa Park, a local park in Istanbul’s Fatih district, after a long and exhausting day. Despite its limited green spaces surrounded by low fences, worn-out benches, untrimmed trees obstructing the pedestrian path, unkempt children’s play areas, and uneven ground, the park emanated a vibrant and dynamic aura. As undergraduate students aspiring to be urban planners, we frequently pondered the concept of public spaces.

On that particular day, our discussion revolved around the general aesthetic issues of the city. As we conversed in a scattered manner, my attention was drawn towards the balconies of the apartments facing the park, which were covered with Pimapen. We scrutinized the mentality behind the unsightly white plastic frame enclosing the balcony, which, in our opinion, was a splendid “zone of liberation” in the context of Istanbul. We were ashamed of those who disregarded the value of spending time on such a balcony.

In reality, this was not the first time I had observed this phenomenon. Six to seven years prior to our discussion, the balcony of my home in Kolej-Ankara was similarly encased and remains so to this day. The same can be said for my mother’s current residence in Kayseri and many other places. This ubiquitous issue was a topic that warranted further contemplation. That night, I made a note of this subject with the intention of revisiting it in the future. And so, for the time being, the topic was set aside.

Clarifying the Problem

In October 2020, a column titled “The Sociology of Pimape” was published in a daily online national newspaper, written by famous sociologist Besim Dellaloğlu. Dellaloğlu begins the text by shedding light on the genericization of Pimapen as a leading brand, just like Selpak (or other globally recognized brands such as Razor, Jacuzzi, Plexiglas, Post-Its, and Xerox -to mention a few examples of my own). He argues that this trend has led to the brand’s replacement of the product. Furthermore, Dellaloğlu suggests that the prevalence of such examples in Turkish society may be due to our limited abstraction abilities (Dellaloğlu, 2020).

In essence, the article elaborates on how PVC has become so widely adopted in Turkey, a phenomenon unique to modernization societies, that have a “world of mindset that over-identifies civilization with technology.” The Pimapen phenomenon has always been a contentious issue for the rapid urbanization process that came with a wave of domestic migration in Turkey. Prior to this, there had been ongoing complaints from the Turkish intelligentsia regarding the search for modernization since the final days of the Ottoman Empire and the manifestations of this search. Nevertheless, the column presents a thought-provoking analysis that could also encompass the phenomenon of closing balconies (Oruç, 2020). As I read the text, it prompted me to contemplate and expand upon the idea further.

Pimapen

Pimapen, a brand established in 1982 that produces PVC (Polyvinyl chloride) joinery materials, is a prominent name in its sector. This construction material is in high demand due to its double-glazed models placed in a white plastic frame, which provide good insulation, ease of installation and use, and relative affordability. Despite the emergence of many rival companies, their competitors were also referred to by the same name.

What makes Pimapen an essential part of Turkey’s urbanization journey is its role in aesthetic debates. Although it has developed several alternative products to the classic white frame, this product is an inseparable part of the city’s skyline, as it is widely used in every newly produced building without any questioning or alternatives. Furthermore, the joinery of houses built before the invention of Pimapen in Turkey is frequently converted to Pimapen, and it even appears on the facades of historical buildings after their controversial restorations.

Drawing on Dellaloğlu’s (2020) observations, there is no other example at the level of fetishism that has adopted this material in any city around the world as much as the citizens of Turkey.

Balcony Culture, Ideologies, and Urbanization

“The balcony means ease, it means pleasure.”

The history of the balcony as a building extension dates back to ancient times. Being an interface between private-public, individual-social, interior-exterior, it appears as an in-between form that resembles both of these two well-defined areas, carries parts of both, but cannot fully represent either. Due to this unique structure, it is seen that it produces a culture that is always referred to as “balcony culture” on its own, and at the same time, it is marked as a manifestation of social culture. Uğur Tanyeli bluntly defines the boundaries of the culture in question with the aspects that he says do not exist in Turkey: “In Turkey, nobody sits on the balcony and sunbathes, has breakfast, reads a book, or has such habits” (Cited in: Üstün, 2020).

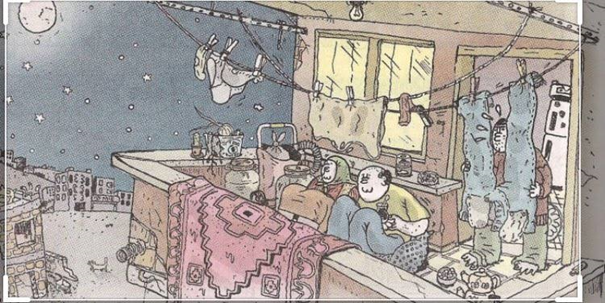

According to internet forums from anonymous accounts, the opposite of the practice of being the place where the carpet is shaken; huge monolith combi boilers, yellow-lidded pickle jars, clothes dryer wire, empty boxes, satellite dishes, viledas, onion-potato baskets, and used as a cellar or warehouse where all kinds of garbage are piled up, while the soldier passing by is celebrating farewell, wedding convoy, circumcision, match “whatever the hell it is,” the bullets of the “chumpheads” shooting into the air were targeted; gazed by someone¹ or gazes ones all day (Löw, 2006) are marked as essential elements of this culture. Accordingly, on balconies designed as a special open space of the buildings designed as residences, virtues such as sunbathing, breathing fresh air and renewing, eating, drinking, socializing, reading, not shaking the carpet, not using it as a warehouse where unused items are piled up, not drying clothes, feeling safe, not watching and not being watched are perceived and accepted as the defining elements of the aforementioned balcony culture.

In terms of balcony usage practices, it is seen that people who determine that there are differences due to geographical location relate the issue to the climate in two different ways. The first claims that climate influences and shapes human character, so it is understandable that some people are more distant from balcony culture than others.

“In İzmir, those who do not sit on the balcony are beaten. But when I lived in Ankara, you would sit on the balcony and turn on the light, and all the cars would turn and look as if there was shit. The steppe is not like that. Our body, which is constantly exposed to the cold, has also affected our soul. If someone had a family conversation on the balcony, laughing and crying, we would blame whatever mood he was experiencing. and on the steppe, no one wants to be blamed.”

The second is that the climate shapes the space, and the concept of the balcony is therefore created out of a spatial need that cannot be adapted to all places. It is seen that there is a common balcony culture in the south and west coasts of Turkey, and in this context, it is common to conclude that this culture cannot even be read in Central Anatolia. Apart from the balcony, sleeping on the roof in the cities of Southeast Anatolia can also be considered as having this culture due to its functional similarity.

When attempting to elucidate why the aforementioned culture failed to materialize, various historical references arise, such as the alleged “incompatibility with the architectural tradition of the Ottoman Empire.” However, the invalidity of assertions such as “there was a closed ‘hayat’ or a sofa instead of a balcony in the traditional Turkish house” can be discerned from the fact that tradition cannot evolve, adapt to the present, and remain unaltered (Yırtıcı, 2020). Despite this, such discourses persist and retain their significance.

The traditionalist perspective portrays the “balcony” as a physical space that predates the “balcony culture”. Consequently, the conservative inclination to preserve privacy² is the principal barrier preventing the balcony’s adoption as a structural extension. The balcony’s gendered nature is a crucial factor in its negative stigmatization as a space that facilitates sensational performances. Hence, instances that highlight the notion of privacy are predominantly gendered, with women being advised to refrain from occupying the balcony.

An Islamist writer contends that the transition from the “cumba (bay window)” to the balcony in traditional Ottoman architecture represents one of the initial steps in the trivialization of family privacy and understanding, “for the sake of Western civilization” (Reyhan, 2013). He suggests that “The concept of balcony, which started with the Tanzimat, is also the opening of the family to the outside and making the house suitable for peeping.” In Namık Kemal’s Vatan Yahut Silistre, Zekiye’s conversation with a man from a balcony was criticized in newspapers and magazines at the time as moral degradation, as evident in the work. The writer considers peeping at home to be the only malicious reason for the change in the social role of women and their liberation. He expresses that “The woman who came out of the peeped houses; gradually becoming an outside person, not a home (in) person, women who first cracked their ‘ar damarı’ (curtain) in the markets as customers; and then in closed spaces (shops) to been material both as a customer and as a seller” (Reyhan, 2013).

It is not surprising that all discussions of privacy are, essentially, centered on women’s struggle to become a public person. The prevalence of the discourse that women should stay at home and become a mother before being a woman reveals the basis of patriarchy’s resistance to the struggle in question. This privacy discourse refers to an agent, which remains ambiguous. As such, it serves as an instructive example of the practice of rewriting history with conspiracies.

In Turkey, the secular segment appears to be aware of the negative stigma associated with religion; however, they still maintain a marginalizing attitude without making an effort to comprehend it. One can frequently come across statements on the internet, such as “religious people” cannot even go near balconies, and the mere mention of “going to the balcony” sends shivers down their spine, thereby portraying balconies as territories of obscurity. These expressions illustrate the construction of a hegemonic counter-discourse aimed at expanding their cultural space-sharing domain.

***

It is possible to encounter opinions that attempt to explain the historical inadequacy of Turkey’s street culture and urban public space as a consequence of the country’s rapid urbanization driven by domestic migration. These perspectives often highlight two main arguments. First, the migrating population has brought their rural customs to the city and has not yet adopted urban values, making it difficult to adhere to the common living rules specific to the city. Second, the migration process is not organized by the state, leading to the construction of unplanned buildings and the failure to establish the physical conditions necessary for developing a culture of living.

Typical examples of the failure to urbanize are cited, such as downstairs neighbors smoking hookah and barbecuing, or upstairs neighbors shaking carpets, which disturb others. While the argument of “un-urbanizable crowds” is typically associated with rural residents, the unplanned urban development argument is supported by the prevalence of air, noise, odor, and image pollution, as well as buildings located too close together due to narrow streets.

Balconies, a characteristic feature of Turkish urban culture, have also come under scrutiny. It is argued that weakening neighborly relations and socialization in virtual channels, as well as the spread of air conditioning, have reduced the demand for balconies. However, during the pandemic, curfew restrictions led to a resurgence of the balcony as a political space for singing, clapping, and playing pots and pans. The intentional use of space can create innovative political and social possibilities and imaginings.

Nonetheless, some commentators are skeptical of the balcony’s revival as a political space, warning of the risk of it becoming a tool for transforming into a police state. Iranian architecture is cited as an example of the lack of interaction between architecture and culture, where the balcony has failed to adapt to changing social needs. However, despite possible cultural incompatibilities, the continued popularity of balconies in Turkey suggests that they still hold value in the country’s urban culture.

The downstairs neighbor smokes hookah, barbecues; carpet shaking of the upstairs neighbor etc. The argument of “crowds that cannot be urbanized” is generally attributed to the countryside, as in the examples of disturbing the neighbor. The unplanned urban development argument is supported by examples such as the prevalence of air-noise-odor-image pollution, and the fact that the buildings are located too close to each other due to the narrowness of the streets. I objected to a friend of mine who explained that it doesn’t feel good to be down with a neighbor while sitting on the balcony, with the argument that “in a cafe there is more distance from people sitting at the next table.” Then my friend replied, emphasizing the temporary character of the cafe, saying that he never had to see those people again, but that he would not want his neighbor to hear everything they said. He continued: “We are afraid that we will go out on the balcony. We are afraid that someone will suddenly get up and cause a mess because they’re looking at my wife and daughter.”

It is said that reasons such as weakening of neighborly relations and socialization in virtual channels reduce the need for physical contact, reducing the demand for balconies. In addition, it is interpreted that balconies have fallen out of fashion due to the possibility that the need for cooling, which is desired from the open air, can also be provided indoors, with the spread of air conditioners. It is also possible to come across comments that the real use of balconies has already been forgotten (Safarkhani, 2016) in different country examples. However, with the curfew restrictions that came to the fore especially with the pandemic process, the need to spend time in the open area and new practices such as singing, clapping, playing pots and pans have emerged. Embodied space and the intentionality of individual and group trajectories do more than create space and place; they also open up space to innovative political and social possibilities and imaginings (Low, 2016: 118). The reappearance of the balcony as a political space³ seems important.

However, there are also commentators who are skeptical of this view. During the curfews brought by the pandemic, the balcony “becomes a control tower where those who are isolated are watching the neighborhood and those who go out against the rules carefully”, and as summarized in the newspaper El Pais, which was published with the headline “The Spain of the balconies is a land of informers”, behind every curtain lurks, attention is drawn to the risk that the balcony will also become a tool for the transformation into a police state (Lamant, 2020).

Arguing that the balcony architecture, which has a completely different style, form, role and usage adapted from a different culture in Iranian residential architecture with Islamic references, is an example of the lack of interaction between architecture and culture, Safarkhani states that the balcony in Iran has failed in this context (2016). Well, if there is a similar cultural incompatibility in Turkey, how can one explain the fact that the balcony is still in demand?

Decision to Close the Balcony: Adding the Balcony to the Room, or Moving the Room Out

The balcony as an element of mass building, which is not included in traditional architecture, is unsuccessful in today’s Turkish cities due to cultural incompatibility; however, the claim that there is a solution to this problem with the action of “closing the balcony” is quite interesting. According to this view, closed balconies recourse to their originality; because the ‘cumba’ was built in old Turkish houses because they served as a closed balcony. Thus, in the structure protruding towards the street, you could watch the surroundings without being seen by others. As it will be remembered, there is privacy in the traditional Ottoman house called “haremlik”, and a controlled partial visibility in favor of the owner in “selamlik”. Although the proposition that the selamlik part, which is built with the protrusions called ‘cumba (bay window)’, inspires the practice of closing the balcony, is interesting, but the claim that it is conveyed with an architectural continuity is unfounded. Because both forms are the product of different contexts and there is no continuity between them. The assumption that there is a functional similarity between them is also questionable. However, it is possible that the attitudes and behavior patterns conveyed through a kind of cultural transmission have revealed similar forms –“…as a creature of habitus, the same body necessarily inhabits places that are themselves culturally informed” (Casey, 1996: 34). In any case, it would be misleading to judge this discussion without further study.

The concept around which this debate on the history of architecture revolves is privacy. Indeed, different people, who seem to be unaware of this discussion, state that they close their balconies with similar concerns. It is perceived as a big problem that the person on the balcony watches the outside and the person outside watches the balcony. It is stated that the behavior described as the “culture of harassment from the balcony” has an effect against the “balcony culture” because “you are surrounded by ‘types’ who sit on the balcony and watch the people all day”. The widespread practice of covering the balcony with reflective or black glass that hides the inside from the outside, which is also in demand in Iran (Safarkhani, 2016), must be related to this.

Although there has not been an academic study on the Turkish case yet, a simple internet research shows that the common secular opinion is in agreement with the conclusion that the balcony closing activity points to a kind of mind-set problem. Accordingly, attempting to close a space designed to be open, unlike a living room, is evidence of lack of vision and ghetto-like behavior. Those who do this are semi-rural types and have not yet been fully urbanized.

The prevalence of essentialist analyzes is also striking. For instance, it is seen that it is described as “one of the manifestations of the features of nomadism, gecekondu (literally put up in one night), degrading the place it is in”, and it is deduced that “we feel a strange pleasure from seizing what does not belong to us”. In further comments, it is pointed out that it is “the result of the expansionist spirit of our people” and that those who are not content with the houses they have; If he lived in an apartment, he closed the balcony and even usurped the distance of 1 meter from the balcony of the neighbor, if he was in a detached house, he expanded the entrance of the house, included half of the common garden in the house, had a new room built, the floor did not rise, etc. allegations are made. It is emphasized that all these acts are signs of property fetishism, cunning and greed.

While it is a definite condition that the house should have a balcony when purchasing, different explanations are encountered on the reasons why the first renovation process after the purchase was to have the balcony closed. The most common of these explanations is about the size issue. When the small size of the balcony does not allow the activities considered as part of the “balcony culture”, a more functional function space is produced by closing the balcony. On the other hand, the smallness of the room to which the balcony is connected brings up the search for closing the balcony or incorporating the balcony into the house in order to have the additional volume needed. In addition, if the balcony faces the rear facade, the well or an area with an unwelcome view (cemetery, etc.), an attempt to close it comes to the fore.

It is stated that people who migrate from rural to urban areas are not provided with the uses they need, so their needs are met by their own methods and means. It is emphasized that the lack of warehouses to store other things such as tomato paste, pickles, dried vegetables, etc., is considered a major problem for people who migrate from the countryside due to their seasonal food production and storage habits, and it is emphasized that closing balconies is a very effective solution.

Another explanation is that even if there is no need for space, it highlights the purpose of using the balcony in summer and winter. They especially emphasize that users who have glass sliding models can fold the glass panels in the summer to create an open space, and in the winter, they can close these panels and enjoy the view with the precautions they take against the cold. Since the assembly of these models is not subject to license (İstanbul İmar Yönetmeliği md.62), they have been in demand in recent years. Similar to other closure practices in this application, “after turning it around, the balcony incident does not have any objective. Open those windows as much as you want, that is not the point!”. In addition, the argument that closing the balcony provides additional insulation (in addition, the greenhouse effect in winter) and thus contributes to the home economy by reducing fuel consumption is quite common.

In addition, as a complementary argument, it is seen that the concerns of protection from heat, insect, dust, UV rays, and glare are also expressed. It may be useful to consider this together with the interpretation that “the demand for access to material comfort and luxury for generations seems to be a social reality beyond ideologies and neighborhoods in Turkey” (Dellaloğlu, 2020). It is also seen to follow a common behavior pattern such as preferring to sit on benches instead of grass in parks, and demanding sunbeds instead of towels for sunbathing on the beach. Therefore, the “state of pollution” that the balcony has due to its nature turns into the reason why the balcony is not preferred on the grounds of hygiene concerns. It is understood that the concern of damaging the furniture on the balcony is also accepted as a valid excuse for closing the balcony. As a precaution, the transformation of the essence of existence comes to the fore.

***

Up to this point, the statements compiled from open and anonymous sources were mostly culturally related. However, it seems inevitable to mention the economic aspect of the issue in order to put its foot on the ground. First of all, it is necessary to look at how property rights correspond to Turkey’s ethos. I am quite doubtful that there is a concept of publicity in the minds of citizens as the definition of property in Turkey. I tried to explain this in detail in the reflection paper I wrote at the beginning of the semester. I will not repeat it here, but it is clear that the way ownership is conceived fosters the sense of absolute ownership that emerges during the balcony closing action. I have already stated that the people I spoke to clearly said “I own the property, I can do whatever I want”.

There is actually legislation in place that prevents them from doing anything they want. According to the Property Ownership Law (Kat Mülkiyeti Kanunu); It is very clear that with the written permission of 4/5 of the floor owners, only glass balconies can be built, and even if the apartment gives approval, the balcony cannot be closed with PVC. It will be remembered that a significant portion of those who benefited from this application in the event we call the “zoning amnesty (imar affı/barışı)” announced the previous year are those who let their balconies in. Although it is clear that balconies taken in against the license will require fines, the prevalence of the practice is not incomprehensible when considered from the point of view of the general functioning problems of the written law in Turkey. This is one dimension of the issue. Another dimension is that the demand for a balcony in newly built houses, although it is clear that it will not be used in Istanbul, is due to a gap in the Istanbul Zoning Regulation (İstanbul İmar Yönetmeliği).

Additional structures such as elevator shafts, fire escapes and balconies are not included in the construction area while calculating the construction area⁴ determined in proportion to the land floor area (İstanbul Büyükşehir Belediyesi, 2018). Therefore, it is clear that converting the gross area of the building into a net area with practices such as closing the balcony or taking the balcony into the house provides an economic gain. Tanyeli describes this situation as “everyone is after the economic return of this. Balcony in Turkey is a small fraud that you do to legally add that balcony to your home.” (cited in: Üstün, 2020) It is striking that this fact becomes evident during the urban transformation projects. Since the net construction area includes the balcony in the new legislation, it is seen that either no balcony is included in the new buildings or dysfunctional uses called “French Balcony” are preferred. Another dimension is related to intellectual property rights. According to the Law on Intellectual and Artistic Works (Fikir ve Sanat Eserleri Kanunu), the building is considered the work of the architect and the architect’s approval is required for any changes to be made on it. However, due to the practice of replicating and implementing sample projects, it is seen that this aspect of the issue is generally ignored.

However, it is also the case that people who have an idea of what it’s like to have a balcony are mourning the balcony they had closed. One online forum writer said,

“We had a beautiful balcony in front of the kitchen. My mother⁵ first covered the balcony with glass five years ago. The effort to add the balcony to the kitchen also yielded results. Kitchen construction has been going on for a week. The result: we no longer have a balcony,. She uses the balconies as a pantry and now he is sad that we do not have a balcony.”

It can be read as a beautiful expression of this contradictory mood. The activity of incorporating the balcony into the house has technical drawbacks beyond an aesthetic problem. Since the floor of the balcony may not be as strong as the other parts of the house, it is unclear what kind of floor problems will be caused by the items that will be piled there in the long run. In addition, in terms of insulation, it makes the apartment even more vulnerable to bad weather conditions.

Finally, it is seen that those who consider closing the balcony as an aesthetic problem draw attention to the incompatibility that occurs on the exterior. Accordingly, determining a common form and expecting the whole apartment to comply with it is presented as a solution. However, it is clear that a field study should be done about it before making an opinion about whether it works or not.

Conclusion

In the study, the social processes that prepared the emergence of the closing balcony phenomenon were discussed. Controversy on today’s examples, especially via social media, were filtered and summarized and a realistic picture of the phenomenon was tried to be drawn.

The social meaning of the balcony was discussed together with its cultural extensions, and it was examined how it functions as an interface. Accordingly, balconies, which are in a state of transition between private-public, interior-exterior individual-collective, appear as a spatial tool of creating places out of space. It has been understood that people who attempt to close the balcony take this action based on two main concerns. The first is privacy concerns; the second is seen as increasing the interior space.

It is obvious that the subject cannot be handled independently of the urbanization and modernization processes of Turkey. It is a notable issue that rural customs were transferred to the city in this process. Due to rural habits, the need for additional space cannot be met in houses built in cities. The act of closing the balcony offers a solution to the need for an extra space, for example, for the storage of foods prepared in the summer for consumption in winter.

Spending time on the balcony is perceived as a bodily performance in Turkey. This seems to be an agreed-upon issue both for the observers and for those being watched. It is also interesting that people say that they prefer to close the balcony to ensure comfort standards. This definition of comfort standard is discussed together with hygiene, protection of furniture from external factors, heat saving, “not being seen but wanting to see” and property rights. It should not be overlooked that the issue also has an administrative dimension at the level of local governments.

It is understood that the habit of closing the balcony, which initially appeared only as an aesthetic problem, indicates a deeper social and cultural background.

Footnotes

¹ “Let me tell you why I sold the house in Şirinevler, I came back tired from work, I open the curtain of the kitchen, in front of me is a belly wearing a tank top… a tea cup in his hand… he looks at me, almost every day…”

² Although it does not seem directly related to this discussion, I suggest to take a look at the text of the decision of the 2014, BIRSEN BERRAK TUZUNATAÇ case as a good example of how the balcony is handled in the context of privacy in modern Turkey: It is beyond the explanation that privacy may be limited due to the fact that life activities can be seen from the outside and these may become public to a certain extent. For this reason, those who want to protect their privacy are expected to limit their living activities on the balcony accordingly. If the person carries the activities that should remain in his private area to the balcony, knowing that they can be seen by others, there is no right to complain that they can be seen by others. Because, the responsibility of protecting privacy and preventing the issues related to the private area from becoming public primarily belongs to the individual. (Constitutional Court, 2014)

³ It is seen that balcony speeches are used by important leaders from the US President Roosevelt to the leader of the Soviet Revolution, Lenin, and even to Erdoğan in our recent political history, to create a sense of belonging in the masses and to excite them. In addition, in Ottoman political history, when subjects, soldiers or party members were disturbed by some issues, they would always come in front of the palace and wait for the Sultan to calm them down with a speech from the balcony (Akgül, 2018).

⁴ Related article: Spaces with at least one open facade, such as open overhangs, balconies, ground, roof and floor terraces, floor and roof gardens, as well as spaces on the same floor or on a different floor, which are annexes of the independent section, and common areas are not considered within the net area of the independent section.

⁵ It is noteworthy that when talking about the balcony, mothers are often referred to among family members. For example, mothers do not like the pleasure of the balcony, because it is in dust, first two buckets of water must be poured, and then glasses / bowls must be carried from the balcony to the kitchen, and mothers are maids because the family will enjoy with the vision of tea seeds on the balcony…

References

Akgül, M.A. (2018) Türkiye siyasetinde iktidarın muktedirliğini ilan etmesinin diğer adı: Balkon konuşmalarının retoriği, Yeniden Sebilürreşad Dergisi, Temmuz 2018, Sayı: 1032, Eylül 2013

Anayasa Mahkemesi (2014) Birsen Berrak Tüzünataç Başvurusu Karar Metni, R.G. Tarih ve Sayı: 14/11/2017–30240, https://kararlarbilgibankasi.anayasa.gov.tr/BB/2014/20364 (date of access: 19.06.2021)

Aydın, D.; Sayar, G. (2020), Questioning the use of the balcony in apartments during the COVID-19 pandemic process, Archnet-IJAR: International Journal of Architectural Research Vol. 15 №1, 2021 pp. 51–63

Casey, E.S. (1996) How to Get From Space to Place in a Fairly Short Stretch of Time: Philosophical Prolegomena, In Senses of Place, edited by Steven Feld, and Keith H. Basso, Santa Fe: School of American Research Press, P.: 13–52.

Dellaloğlu, B. (2020) Pimapenin Sosyolojisi, Gazete Duvar, https://www.gazeteduvar.com.tr/pimapenin-sosyolojisi-makale-1500992 (date of access: 20.06.2021)

Ecer, H. (2020) Balkonun yaşama katılması, Gazete Duvar, https://www.gazeteduvar.com.tr/forum/2020/05/09/balkonun-yasama-katilmasi (date of access: 20.06.2021)

Esener, Ö.; Deniz, Ö.S. (2018) Bi̇na Cepheleri̇nde Oluşan Tasarım Kaynaklı Bozulmaların İncelenmesi̇, Yalıtım Dergisi, Oct-2018, pp: 38–46

İstanbul Büyükşehir Belediyesi (2018) İstanbul İmar Yönetmeliği, Resmi Gazete- Tarih: 20 Mayıs 2018 Pazar, Sayı: 30426, https://www.resmigazete.gov.tr/eskiler/2018/05/20180520-4.htm (date of access: 19.06.2021)

Karabulut, M. (2016) Balkon Sefası, Gazete Bursa, 14 Haziran 2016, https://www.gazetebursa.com.tr/balkon-sefasi-makale,647.html (date of access: 19.06.2021)

Lamant, L. (2020) Balkonun siyasal tarihi, Çev.: Ayşen Uysal & İnci Malak Uysal, Medyascope, 1 Nisan 2020, https://medyascope.tv/2020/04/01/ludovic-lamant-balkonun-siyasal-tarihi/ (date of access: 20.06.2021)

Low, S. (2016) Embodied Space -chapter 5, p: 94–118, in Spatializing Culture: The Ethnography of Space and Place. Routledge.

Löw, M. (2006) The social construction of space and gender. P. Knowlton (trans.) in European Journal of Women’s Studies, vol. 13(2) : 119–133.

Oruc, R. (2020) Pimapenin Sosyolojisi, personal blog post on Medium, https://bit.ly/3gY713j (date of access: 20.06.2021)

Reyhan, M.F. (2013) Ölümün Cesur Körfezi “Balkon” Bir Semboldür, İlkadım Dergisi, https://ilkadimdergisi.net/arsiv/yazi/olumun-cesur-korfezi-balkon-bir-semboldur-208 (date of access: 19.06.2021)

Safarkhani, M. (2016) Balconies Consigned to Oblivion in Iranian Residential Buildings the Case of Tehran, Iran, Unpublished Master Thesis, METU

Üstün, S. Küçük bir sahtekârlıktır Türkiye’de balkon, blog post on one’s personal website, https://suleymanustun.com/kucuk-bir-sahtekarliktir-turkiyede-balkon (date of access: 20.06.2021)

Various Users (2021) Balkon Kapattırmak, on eksisozluk.com, https://eksisozluk.com/balkon-kapattirmak--856824 (date of access: 20.06.2021)

Yırtıcı, H. (2020) Balkon: Konut mimarisinin üvey çocuğu, Gazete Duvar, 14 Mayıs 2020, https://www.gazeteduvar.com.tr/yazarlar/2020/05/14/balkon-konut-mimarisinin-uvey-cocugu (date of access: 19.06.2021)

Comments

Post a Comment